“The fact that customers come to the club and choose me means they’re coming because I’m there,” Gaish tells the camera. “I know that, even if it’s just a tiny bit, I’m in her thoughts… I like people who really need me.”

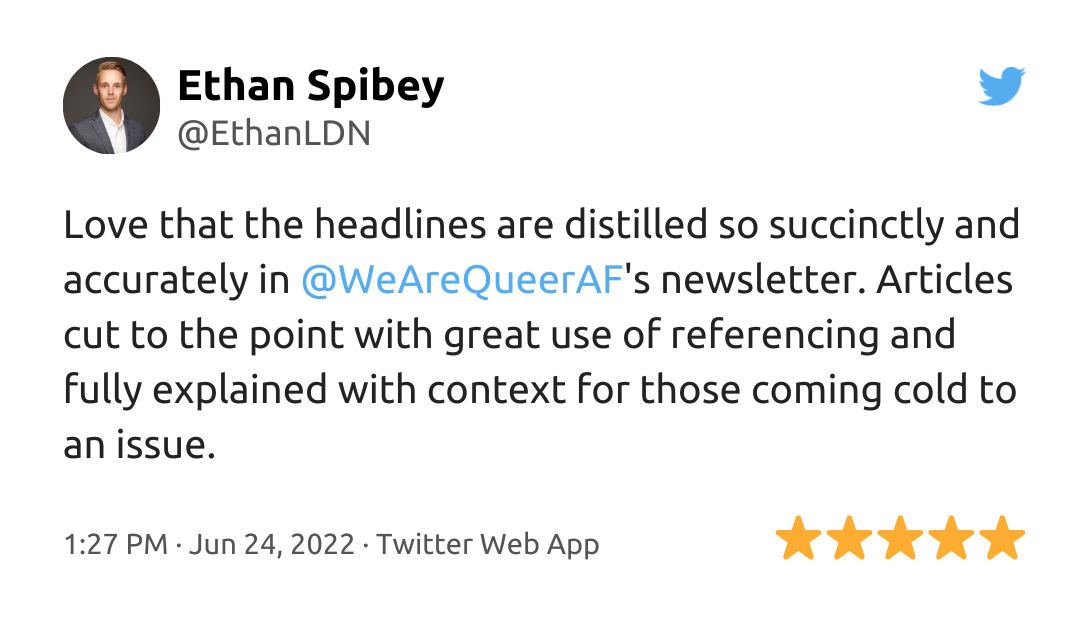

Beneath the flashing lights and Marlboro ads of late 20th-century Tokyo, a tiny community carves out a place for itself.

At the New Marilyn club in neon-studded Kabukicho, the three hosts prepare for their night: Standoffish Gaish models his sunglasses, lovable Kazuki binds his chest, dapper Tatsu gets a pre-work trim-up and discusses hormones with his barber.

The host club, where they are paid to drink, socialise, and flirt with women patrons, doesn’t look like much, but to these three it’s home.

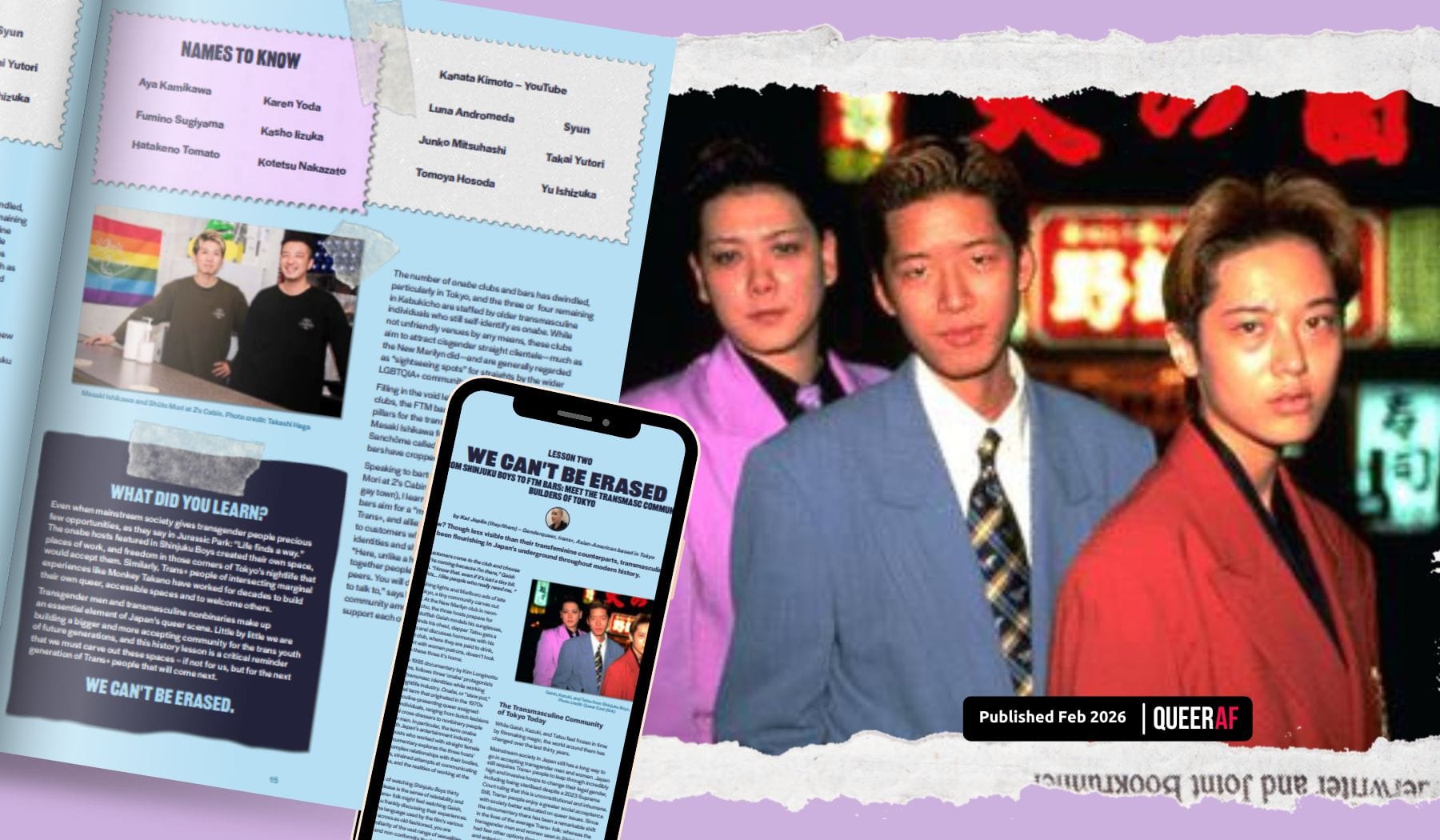

Shinjuku Boys, a 1995 documentary by Kim Longinotto and Jano Williams, follows three ‘onabe’ protagonists navigating their transmasc identities while working Tokyo’s rough nightlife industry.

Onabe, or “stew pot,” is a now-outdated term that originated in the 1970s to describe masculine-presenting queer assigned-female-at-birth individuals, ranging from butch lesbians and professional cross-dressers to nonbinary people and transgender men.

In particular, the term onabe is associated with Japan’s entertainment industry, particularly for hosts who worked with straight female patrons.

The documentary explores the three hosts’ personal lives, complex relationships with their bodies, gender identities, strained attempts at communicating with their families, and the realities of working at the New Marilyn.

The great magic of watching Shinjuku Boys thirty years after its release is the sense of relatability and commonality Trans+ folk might feel watching Gaish, Kazuki, and Tatsu frankly discussing their experiences.

While some of the language used by the film’s various subjects comes across as old-fashioned, you are struck by the familiarity of the vast range of sexualities, gender identity, and nonconformity the three express.

Even when mainstream society gives transgender people precious few opportunities, as they say in Jurassic Park: “Life finds a way.”

The onabe hosts featured in Shinjuku Boys created their own space, places of work, and freedom in those corners of Tokyo’s nightlife that would accept them. Similarly, Trans+ people of intersecting marginal experiences like Monkey Takano have worked for decades to build their own queer, accessible spaces and to welcome others.

Transgender men and transmasculine nonbinaries make up an essential element of Japan’s queer scene. Little by little we are building a bigger and more accepting community for the trans youth of future generations, and this history lesson is a critical reminder that we must carve out these spaces - if not for us, but for the next generation of Trans+ people that will come next.

Time to do the workbook

The 2026 Trans+ History Week workbook is the ultimate toolkit for shutting down lies about Trans+ people

This year, QueerAF produced the workbook for Trans+ History Week. We mentored five Trans+ researchers and writers to put it together through over 80 hours of research.

That work was spearheaded by lead researcher Gray Burke-Stowe, who ensured the stories have accurate and rich historical sources.

Download it now to immerse yourself in stories of the Lango people of Uganda or the legacy of Miss Major, tracing back to Comptons Cafeteria.

Or maybe you're intrigued by how gender diversity has shown up throughout history, or the trans masc (no longer) underground scene in Tokyo?

Get your copy now, to help us get the word out: We've always been here, we can't be erased, we're more than Trans+, and crucially, we're stronger together.