Does trans media have an obligation to explicitly label its trans characters as such?

Consider Jane Schoenbrun’s 2024 release I Saw The TV Glow. A “deeply trans movie”, the film directly confronts the ‘egg-crack’ moment of irreversible change in the wake of realising that one is transgender.

But the word ‘transgender’, or any of its older variants, is not used once in the entire film. Nor is it applied to the main characters Owen and Maddie, even though, as we come to realise, it would probably describe them well enough.

Instead, the film takes a more lateral approach to queer identity: when Owen is asked if she likes boys or girls, she sidesteps the question entirely and responds “I think… I like TV Shows”.

The absurdity of her response is a gag, but it simultaneously speaks more broadly to the experience of being so terrified of your own identity that even direct prompts toward it can be met only with a radical subject change. Owen’s characterisation as transfem rests on a gradual accumulation of implicit moments like these, rather than the film ever explicitly labelling her transgender.

Historically, this approach to a queer character’s identity has been necessitated by queerphobic censorship practices. Books that dealt with queerness in a way that was deemed ‘too’ explicit, such as Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness or James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, were subject to obscenity laws that could see them banned on a regional or national level and the publisher fined to discourage them from platforming similar work in future.

Authors also had to fear the personal consequences of being publicly associated with queerness by their work. When Oscar Wilde was convicted of ‘gross indecency’ for being gay, his homoerotic book The Picture of Dorian Gray was used as evidence against him.

While queerphobic censorship does persist in some countries and regions, queer activists have worked hard to bring about societies where explicitly queer media is no longer legally persecuted.

In that context, the creative choice to leave queerness as subtext might seem odd, or even ungrateful. Don’t we have an obligation to make the most of the rights that past generations of queers carved out for us?

In the case of I Saw The TV Glow, a substantial portion of the film’s audience had interpretations of the film that marginalised its transness, or missed or ignored it entirely.

Perhaps explicit labels would have been beneficial: after all, when films that represent the trans community are so exceedingly rare, can we really afford to lose one to miscommunication?

To some extent, this discussion might come down to a question of what Trans+ representation is for, and whether all Trans+ representation is for the same thing.

There is certainly a need for Trans+ media that makes its Trans+ status impossible to miss, especially at a time when the Trans+ community is being increasingly suppressed. But there is also a need for representation like I Saw The TV Glow.

Someone who does not yet identify with the label “transgender” will immediately perceive a character labelled “transgender” as being other than them, and will probably close themselves off to the possibility that the film that centres on that character could be about them.

But if the same person has the experiences of that character demonstrated to them without the use of any particular label, they will be left to draw their own conclusions about the extent to which they might relate, and the implications that could have on their identity.

In fact, dozens of people have reported that watching I Saw The TV Glow either allowed them to come to the realisation that they are transgender - even if they had never really considered the possibility before - or helped them move past their denial over their gender identity and start transitioning. Given that context, the fact that I Saw The TV Glow’s style of representation is relatively rare becomes all the more regrettable.

Overall, it should be recognised that not all examples of Trans+ representation work in the same way. If the ultimate goal of representation is to allow every person of every combination of identities to encounter their own reflection, then there needs to be space at the mirror, too, for those still learning to see themselves.

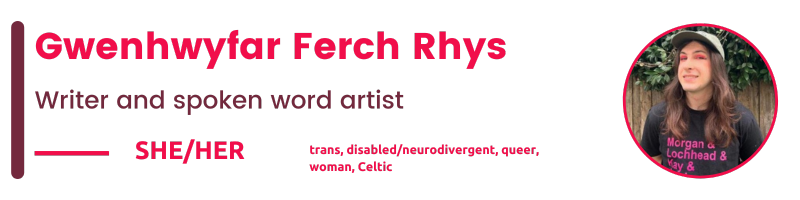

This article is part of a QueerAF and Inclusive Journalism Cymru partnership dedicated to uplifting Welsh LGBTQIA+ emerging and marginalised journalists.

Get the Queer Gaze in your inbox each week with our free weekly newsletter or pitch to write an edition for us now.

QueerAF has partnered with Inclusive Journalism Cymru.

Together we're running a dedicated series of think pieces as part of a unique set of Queer Gaze commissions - our landmark writing scheme.

The articles are being written by three LGBTQIA+ journalists from Inclusive Journalism Cymru's network.

The Queer Gaze is a space in the QueerAF newsletter to commission emerging and underrepresented queer creatives to get published, receive mentorship, and kickstart your career.

Each commission comes with a unique 'retrospective' sub-editing session designed to put you in control of your article.

It's helping Welsh LGBTQIA+ creatives build journalistic craft and strategic communication skills.

You can support our work by becoming a QueerAF member.